|

|

Full-Mouth Rehabilitation and Bite Management of Severely Worn Dentition

Released on: March 30, 2009, 8:27 am

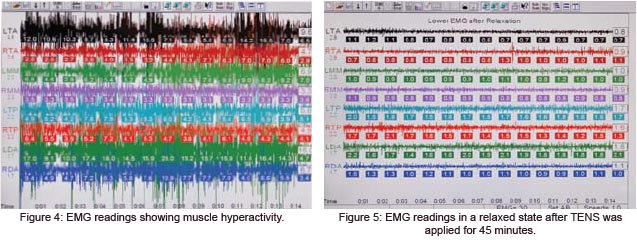

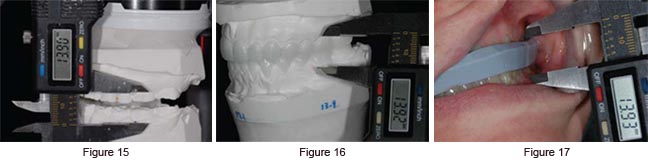

The case presented here was featured on the cover of the Spring 2008 issue of The Journal of Cosmetic Dentistry. While it was quite challenging, I will never forget this case,, as it changed the life of a recovering bulimia patient. Eating disorders affect approximately seven million people in the United States. Although I have seen the effects of bulimia on the dentition previously, never have I witnessed it to this extent. The patient was diagnosed with loss of vertical dimension as a direct result of bulimia and bruxism. Patient History Clinical Evaluation and Diagnosis The patient suffered from many typical symptoms of temporomandibular disease (TMD), such as joint pain, severe headaches, tinnitus, and orofacial muscle pain with spasms.1 These symptoms were not surprising, as craniomandibular dysfunction is often seen with loss of vertical dimension. She was also a severe bruxer and said this provided her with relief. Due to this vertical loss, the lower third of her face was collapsed and disproportionate. The patient was diagnosed with loss of vertical dimension as a direct result of bulimia and bruxism; this was accompanied by multiple fractured, eroded teeth, and worn restorations. Additionally, the patient had facial asymmetry and multiple TMD symptoms due to craniomandibular dysfunction.2 She tolerated the orthotic well and felt much better with it in place. Treatment Plan During this time, her condition would be evaluated for elimination of symptoms, proper occlusion, improvement in facial symmetry, esthetics, and acceptable phonetics. If we had not seen improvements during the orthotic phase, the first thing we would have looked at was compliance. If it had been determined that the patient was not wearing the appliance as instructed, or if the therapy had had to be extended beyond three months (due to inconsistent symptoms or an unstable bite position), we would have used a fixed orthotic appliance, which would have been fabricated to the same vertical dimension as the removable orthotic.4 The goal, for any clinician, is to find a position in which the patient’s symptoms are eliminated, or at least decreased significantly. The facial and dental esthetics also must be greatly enhanced. Although there is more than one way to find this physiologic position, in this case I objectively measured muscle activity by using electromyography (EMG) instrumentation (Myotronics-Noromed; Kent WA). This enabled me to locate the correct resting position for the mandible where the muscles are at rest, as well as the correct opening and closing trajectory.5 During the course of orthotic phase therapy, which can last several months to a year, the patient returns to verify the bite and evaluate symptoms several times. Once it is determined that the patient is comfortable, facial esthetics are improved, and the EMG muscle activity is verified to be physiologic, then the restoration phase can begin.6,7 Treatment Discussion Finding the Bite To find a more optimal bite position, a series of diagnostic tests were performed. These included electrosonography to record and analyze joint sounds, electromyography to record and analyze muscle activity, and computerized mandibular scanning (CMS) to track and analyze jaw movements. It was determined that the patient’s habitual occlusion was in a muscular state of hyperactivity when at rest and in light centric occlusion (Fig 4). In order to relax her muscles, which were in a chronic spasmodic state, ultra-low frequency transcutaneous electrical neural stimulation (TENS) was applied using a myomonitor (Myotronics). The myomonitor stimulates cranial nerves V, VII, and XI to relieve hypertonicity, restore normal blood flow, and wash away toxic wastes such as lactic acid. This restores the muscles temporarily to a relaxed and normal resting length (Fig 5). These muscles become “deprogrammed,” and, by measuring their pre- and post-relaxation status, we are provided with precise and objective comparative data.10,11 The details of all the tests performed during the three-hour diagnostic appointment are beyond the scope of this article. The position at which this patient’s muscles were in their most relaxed state was captured by using a polyvinyl siloxane bite registration material (Regisil, Dentsply Caulk; Milford, DE). Impressions were then taken (Aquasil Ultra, Ivoclar Vivadent; Amherst, NY) and sent to the laboratory with the bite to fabricate a lower removable orthotic. Upon delivery of this appliance, I explained to the patient that it must be worn a minimum of 22 hours a day. Each follow-up visit always consisted of 45 minutes of TENS, followed by any necessary occlusal adjustments to the orthotic. The patient was seen at one-, two-, three-, four-, and sixweek intervals. She tolerated the orthotic well and felt much better with it in place; therefore, compliance was not an issue.12,13 Once it was determined that the bite was stable and that symptoms were significantly reduced, EMG recordings were taken again to verify that the muscles were not hypertonic in this new position. In this case the EMG readings were more than satisfactory, and the patient’s headaches and other symptoms were reduced significantly. Therefore, I had great confidence as to where to restore her occlusion.14 Her bite was opened 4 mm. The next phase of treatment was the restorative phase. Bite Management Once the laboratory mounted the casts with the adjusted orthotic in place and the three measurements were verified, a bite stent (Sil-Tech, Ivoclar Vivadent) was made, to be utilized during the preparation appointment to ensure accuracy in maintaining the new vertical dimension. The appliance was then immediately returned to the patient so that she could continue to wear it. The laboratory also was provided with detailed instructions concerning the smile design, including widths and lengths of anterior teeth, shapes, and proportions.15 Because the patient’s maxillary anterior teeth were short, it was determined that crown lengthening was necessary to support the restorations. Therefore, the proposed amount of hard and soft tissue removal was relayed to the laboratory so that they could compensate for the change in measurement in this area. With this information in hand, they waxed up the 28 teeth in the new position, taking into consideration the hard and soft tissue reduc-tion in the anterior; and once again verified the three measurements (Fig 10). From this wax-up, they prepared a temporization stent made from Sil-Tech putty and relined with a light-body wash material (Aquasil XLV, Dentsply Caulk). This would be used to fabricate the 28 temporaries after tooth preparation, with the same vertical dimension and occlusion as the orthotic. Bite Management After the patient was seated, I verified the bite stent that had been made on her unprepared, mounted models by placing it in her mouth and having her close down on it. I again measured the same three locations and verified that those measurements were the same as they were with the orthotic in place (Fig 11). I was confident that all of my numbers were accurate, so it was time to begin preparing the teeth. It was imperative not to lose control of the bite at any time during the preparation. After anesthetizing the patient, the first step was to perform the soft and hard tissue crown lengthening in the maxillary anterior region to improve the length of her short clinical crowns. To accomplish this, I used an Er,Cr:YSGG hard/soft tissue laser (Waterlase, Biolase Technologies; Irvine, CA) and at the same time performed a frenectomy between the maxillary central incisors. Using this laser provided a predictable result and gave me a clean field within which to work. I removed 1.2 mm of tissue and therefore changed the location of my uppermost point for measurement after the crown lengthening. I had to adjust my number for verification from this point on, in this area only16 (Fig 12). It was imperative not to lose control of the bite at any time during the preparation. To help in maintaining this vertical dimension, I used the bite stent provided by the laboratory to sequentially reline it while I prepared one quadrant at a time. Beginning with the upper right quadrant, I prepared ##3-8, while leaving #2 unprepared to provide extra stability while I relined the bite stent. To register the bite, I sat the patient upright and placed a small amount of fast-setting bite registration material (Regisil Rigid) in the bite stent, being careful not to overfill it and to reline only the prepared teeth. This was then placed in the mouth with the patient biting into it. While the stent was in her mouth, the same three locations were measured again, remembering that the anterior area had a new measurement. If the measurements had not matched those taken previously it would have been necessary to repeat the reline, as the patient might have been biting incorrectly or the bite stent might not have been seated over the teeth properly. Once it was determined that the measurements were correct, the stent was removed, trimmed, and set aside for the next quadrant. The same procedure was repeated for the upper left quadrant, preparing ##9-14 and leaving tooth #15 unprepared. This quadrant was then relined the same way. After the measurements were verified, I prepared #2 and #15 (Fig 13). This procedure was repeated for the bottom right quadrant and then the bottom left. A final check of the measurements was made and the bite stent was set aside to send to the laboratory along with final impressions. For these, I used a PVS heavy-body material and an extra-low viscosity wash material (Aquasil Ultra-heavy and XLV). A symmetry bite was also taken, indicating to the laboratory the proper occlusal plane and midline. Photographs of the preparations, which showed the measurements with the final bite stent seated and with the symmetry bite in place, were provided for the laboratory. Temporization Laboratory Communication For the smile design, we decided on a “soft” look with square oval central incisors and slightly rounded laterals and canines, with the lateral incisors 0.5 mm shorter than the centrals. The requested width of the central incisors was 8.25 mm and the length was 10.75 mm. The lateral incisors were approximately 10.25 mm long. Golden proportion rules and smile design principles were adhered to, which provided the patient with a very soft and esthetically pleasing smile. Our final shade choice was OM2 body with a cervical blend to OM3 (Vita 3D Master shade guide), with the canines blending from OM2 to 1M1 cervically. We selected Authentic pressable ceramic (Jensen Indus-tries; North Haven, CT) for all anterior teeth and bicuspids, using an OP1+ ingot with cutback technique and adding intense opaque modifiers to increase vitality and a natural appearance (Fig 14).18 All of the molars were restored with Noritake CZR pressable ceramic (Zahn Dental, Henry Schein; Melville, NY) over zirconia copings.19 The #5 implant was restored with a custom abutment with Creation porcelain (Jensen Industries). Prior to the fabrication of the restorations, the models were mounted using the preparation bite stent, and all the measurements were verified by the laboratory (Figs 15-18). Cementation Once we were satisfied with restorations, they were cleaned with 37% phosphoric acid, rinsed, dried, and set aside. The molars were cemented first using Multilink (Ivoclar Vivadent), a self-etching universal resin cement, with the inside of the restorations coated with the metal/zirconia primer (Ivoclar Vivadent). Then all of the remaining upper teeth except #5 were etched with 37% phosphoric acid and rinsed, after which a wetting agent was applied (Super Seal, Phoenix Dental; Fenton, MI).20 Then the bonding agent (Excite, Ivoclar Vivadent) was placed on the teeth according to manufacturer’s directions and light-cured. The restorations, which had previously been etched with hydrofluoric acid, were coated with Silane primer (Kerr; Orange, CA). The luting resin used for cementation was Variolink Veneer +2 (Ivoclar Vivadent). All of the restorations were placed simultaneously and spot-cured. The excess was then removed, followed by the final light-cure. Tooth #5 was cemented with implant cement (Premier Dental; Plymouth Meeting, PA).21 The same technique used on the maxillary teeth was applied to the lowers. Once all teeth were cemented, the three measurements were once again verified to confirm maintenance of the vertical dimension (Fig 19). The patient returned for follow-up appointments to make sure her bite was stable and that she remained symptom-free. Conclusion and Discussion I conducted a series of diagnostic tests using computerized instrumentation, which provided me with objective data that I was able to use in my treatment planning. The key point is that this patient initially exhibited severe occlusal disharmony and craniomandibular dysfunction. This can be the case in many of our patients, and much effort should be spent in proper diagnosis and treatment planning.22 I did not prepare 28 teeth in one visit and deliver them a few weeks later. Instead, I conducted a series of diagnostic tests using computerized instrumentation, which provided me with objective data that I was able to use in my treatment planning. Not until the patient’s new vertical dimension position was tested for several months did I dare touch a single tooth with a handpiece. Once I did, however, it was with great confidence, because I knew in which direction I was headed (Figs 20 & 21). It is well accepted that there is more than one philosophy or method that can be utilized to arrive at a physiologic bite position. A discussion of these different philosophies— whether centric relation, centric occlusion, or neuromuscular—is beyond the scope of this article.23 However, as responsible clinicians, we should study the different treatment modalities available to our profession before making a decision as to which one suits us. Whichever method you apply in your practice, the most important factor is that it must be in your patients’ best interests.24 Before proceeding to final restorations, it is imperative to establish a comfortable, stable bite derived from verifiable, objective clinical data (Figs 22-29). Acknowledgments References 2. Coy RE, Flocken JE, Adib F. Musculoskeletal etiology and therapy of craniomandibular pain and dysfunction. Cranio Clin Int 1(2):163-173, 1991. 3. Jankelson RR. Neuromuscular Dental Diagnosis and Treatment. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Ishiyaku EuroAmerica; 2005. 4. Naeije M, Hansson TL. Short-term effect of the stabilization appliance on masticatory muscle activity in myogenous craniomandibular disorder patients. J Craniomand Disord Facial Oral Pain 5:245-250, 1991. 5. Ormianer Z, Gross M. A 2-year follow-up of mandibular posture following an increase in occlusal vertical dimension beyond the clinical rest position with fixed restorations. J Oral Rehab 11:877-883, 1998. 6. Liu ZJ, Yamagata K, Ito G. Electromyographic examination of jaw muscles in relation to symptoms and occlusion of patients with TMJ disorders. J Oral Rehab 26(1):33-47, 1999. 7. Neill DJ, Howell P. Computerized kinesiography in the study of mastication in dentate subjects. J Prosthet Dent 55(5):629-638, 1986. 8. Mongini F, Tepia-Valenta G, Conserva E. Habitual mastication in dysfunction: A computer-based analysis. J Prosthet Dent 1:484-494, 1989. 9. Jankelson B. Three dimensional orthodontic diagnosis and treatment: a neuromuscular approach. J Clin Orthod 18(9):627-636, 1984. 10. Ow RK, Carlsson GE, Jemt T. Craniomandibular disorders and masticatory mandibular movements. J Craniomand Disord Facial Oral Pain 2(2):96-100, 1988. 11. George J, Boone M. A clinical study of rest

position using the kinesiograph and myomonitor. 12. Konchak P, Thomas N, Lanigan D, Devon R. Freeway space using mandibular kinesiography and EMG before and after TENS. Angle Orthod 58(4):343-350, 1988. 13. Balciunas BA, Stahling LM, Parente FJ. Quantitative electromyographic response to therapy for myo-oral facial pain: A pilot study. J Prosthet Dent 58:366-369, 1987. 14. Isberg A, Widmalm S, Ivarsson R. Clinical, radiographic, and electromyographic study of patients with internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint. Am J Ortho 88(6)453-460, 1985. 15. Griffin JD. How to build a great relationship with the laboratory technician: Simplified and effective laboratory communications. Contemp Esthet 10(7):26-34, 2006. 16. Colonna M. Crown and veneer preparations using the Er,Cr:YSGG Waterlase hard and soft tissue laser. Contemp Esthet Rest Pract 10:80-86, 2002. 17. Bengel W. Mastering Dental Photography Hanover Park, IL: Quintessence Pub.;2002. 18. Magne P, Belser U. Bonded Porcelain Restorations in the Anterior Dentition: A Biomimetic Approach. Hanover Park, IL: Quintessence Pub.; 2002. 19. Ludwig K. Studies on the ultimate strength of all-ceramic crowns. Dent Laboratory 39:647-651, 1991. 20. Kanca J. Improving bond strength through acid etching of dentin and bonding to wet dentin surfaces. JADA 123:35-44, 1992. 21. Garg AK. Practical Implant Dentistry (1st ed.). Dallas, TX: Taylor Publishing; 2007. 22. Tingey EM, Buschang PH, Throckmorton GS. Mandibular rest position: A reliable position influenced by head support and body posture. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 120(6):614-622, 2001. 23. Pully ML, Carr S. Solving the pain puzzle:

Myofascial pain dysfunction (3rd ed.). Albuquerque,

NM: TMData Resources; 1997.

24. Shankland WE . Temporomandibular disorders:

Standard treatment options. Gen

Dent 52(4):349-355, 2004. Contact Details: Dr. H.R. Makarita DDS,MAGD

|

|